- Home

- Simon Rose

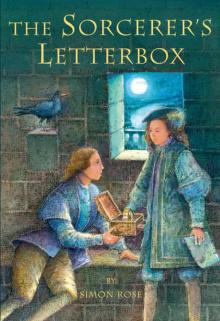

The Sorcerer's Letterbox

The Sorcerer's Letterbox Read online

VANCOUVER LONDON

This ebook is licensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not be re-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to share this book with another person, please purchase an additional copy for each recipient. If you’re reading this book and did not purchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then please purchase your own copy. Thank you for respecting the hard work of this author.

Tradewind Books

www.tradewindbooks.com

Text copyright © 2004 by Simon Rose

Cover illustration © 2004 by George Juhasz

Book design by Jacqueline Wang

Published as an ebook in 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior written permission of the publisher or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright, The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency, 1 Yonge Street, Suite 800, Toronto, Ontario M5E 1E5

The right of Simon Rose to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988.

Cataloguing-in-Publication Data for this book

is available from The British Library.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Rose, Simon, 1961-

The sorcerer’s letterbox / by Simon Rose.

ISBN 1-896580-52-1(print)

ISBN 978-1-926890-52-4(ebook)

I. Title.

PS8585.O7335S67 2004 jC813’.6 C2004-901410-2

This book is dedicated to Lizzie. I’ll never forget you.

—S.R.

Map (overleaf)

Plan of the Tower of London, from a print

published by the Royal Antiquarian Society

and engraved from the survey made in 1597

by W. Haiward and J. Gascoigne

by order of Sir J. Peyton, Governor of the Tower,

published in London, edited by Charles Knight, London, 1842

The publisher thanks Sian Echard

for her translation into Middle English.

Tradewind Books thanks the Governments of Canada and British Columbia for the financial support they have extended through the Canada Book Fund, Livres Canada Books, the Canada Council for the Arts, the British Columbia Arts Council, Creative BC and the British Columbia Book Publishing Tax Credit program.

Map

Plan of the Tower of London, from a print published by the Royal Antiquarian Society and engraved from the survey made in 1597 by W. Haiward and J. Gascoigne by order of Sir J. Peyton, Governor of the Tower, published in London, edited by Charles Knight, London, 1842.

Contents

Prologue

I. The Message

II. The Letterbox

III. Edward

IV. The Mission

V. Uncle Richard

VI. The Tunnel

VII. The Outlaws

VIII. The Forest Hide-out

IX. Return to the Tower

X. Putting the Pieces Together

XI. Cheating Fate

XII. Into the City

XIII. Breaking Into Prison

XIV. The Lion’s Den

XV. The Stolen Crown

XVI. Flight to the Future

XVII. A Twist in Time

XVIII. The Two Mr. Kings

Prologue

England 1470

Brother William gazed into the ball of polished glass. Tantalizing glimpses of the future, shrouded in mist and shadows, flickered and disappeared. Carefully, he put the ball back into its velvet sack and ran his fingers over the exquisitely decorated box in front of him. It perfectly matched the image that he had just seen.

He heard footsteps coming up the stairs. That must be the queen, he thought, opening the door. She has come at last.

“Your Majesty,” he said, bowing as she swept into the room.

“Brother William, I presume,” said the queen.

“Yes, Your Majesty.”

She walked over to the tiny window and peered down at the unmarked carriage waiting below.

“I risk a great deal coming here,” said the queen, lowering the hood of her cloak. “My enemies have spread rumours that I practise the dark arts. My own brother-in-law, the duke of Gloucester, believes that I bewitched the king into marriage. It will do me no good if I am seen with you in this inn. It is said you are a sorcerer.”

“Your Majesty,” protested Brother William, “I am but a humble monk.”

“You were a monk,” the queen corrected him, as she sat at the table. “I know your story, Brother William. You were banished from the monastery, and now there is a price on your head.

“Your messenger said you had a vision that harm would come to my son and that you would give me something to protect him.” She pointed to the box. “Is this it?”

“Indeed it is, Your Majesty.”

With trembling hands, Brother William gently pushed the box across the table toward her. The queen studied the painted figures on the sides, lifted the lid and peered in.

“It seems an ordinary box to me. My son’s christening is on the morrow. What more can you tell me?”

Brother William shook his head. “One day the prince will be in grave danger; this box will protect him. He must always keep it close at hand.”

“But how does it work?”

“When danger is near, he must place a letter inside the box, and it will bring him aid when he most needs it.”

“You speak in riddles, old man!” snapped the queen, grabbing the box. “I can tarry no longer.”

Without a backward glance, she hurried from the room, clutching the box tightly under the folds of her cloak.

Brother William quickly gathered up the velvet sack and prepared to leave. Moments after the queen’s carriage departed, he heard a loud pounding at the door and shouts from the street below. It was the sheriff’s men.

By the time they reached the upstairs room, Brother William had disappeared.

The Message

I

Jack lay awake in a dimly lit room with carved stone walls and a single arched window. Moonlight illuminated the outline of a sleeping boy in a bed against the far wall. The door to the room creaked open, and the shadow of a man silently moved toward the sleeping boy. Jack gasped as the shadowy figure turned, revealing a gruesome scar where the man’s left eye should have been.

“Come to breakfast, Jack!” his mother called from downstairs. “It’s your day to help Dad at the shop.”

Jack woke with a start, gasping for breath. He couldn’t remember the last time he’d had such a terrible nightmare. He shook it off, rolled out of bed and stooped to pick up the history book he’d been reading when he fell asleep. He’d just started a chapter about Richard III and the Princes in the Tower.

Jack set the book down on the desk, next to a small antique wooden box that had been in his family for generations. The box looked medieval, with faded artwork on the sides and lid. Glancing at the box, Jack noticed that the drawer in the base, which had always been stuck closed, had popped out slightly. It was stiff, but he managed to tug the drawer open.

Inside lay a small roll of parchment tied with a silk ribbon. Slipping off the ribbon, Jack carefully unrolled the scroll and spread it out on his desk.

I wonder how long it’s been in the drawer, Jack thought. The paper doesn’t look that old.

Jack recognized the wri

ting as Middle English, but to him, it was like a foreign language.

Dad might know how to read this.

His father had an antique shop in the village where they lived. The shop had a small collection of medieval documents with similar writing. It was the final week of school holidays, and Jack had been helping his father at the shop all summer.

He rolled up the parchment, got dressed and headed downstairs for breakfast.

“Morning,” said Jack’s mother, as she poured herself a fresh cup of tea.

“Didn’t think you were going to make it,” added his father, looking up from his newspaper.

“Sorry,” Jack apologized. “I didn’t sleep very well.”

“Burning the midnight oil again?” asked his father, peering at him over the morning headlines.

His mother placed a plateful of toast in the middle of the table.

“Just because we allowed you to grow your hair doesn’t mean that we’ve relaxed the rules about bedtime too,” she said.

“Okay, okay.”

Turning to his father, Jack held up the scroll and said, “Remember that old box you gave me? I found this in its drawer. It looks like it’s written in Middle English.”

“That drawer has never opened before,” his father said, putting down the newspaper. “Let me have a look at that.”

Jack handed him the scroll. His father unrolled it and spread it out on the table.

“The script does look like Middle English, Jack, but the parchment seems new.”

“You two had best get moving,” Jack’s mother said, “or you’ll be late opening the shop.”

“That’s right,” said his father, looking at his watch. “Come on, Jack, and bring that scroll along. We’ll see if we can figure out what it says.”

Jack nodded and hurried after him out the door.

“Didn’t you tell me that the box was once owned by the king of England?” Jack asked as they got into the car.

“If I had a penny for every time I heard a story like that about an antique, I’d be a rich man.”

“So it’s not true?” Jack asked, disappointed.

“Could be. But in my experience, when it comes to antiques, the more fabulous the story, the less likely it is to be true. All I know for certain is that the box has been in our family for generations, but nobody knows where it originally came from.”

As they drove through the village, they passed The Sorcerer, an inn dating back to the Middle Ages. A colourful sign hung over the door. It depicted a white-bearded old man dressed in a dark robe embroidered with gold stars. According to local legend, a mysterious monk who dabbled in the supernatural had once lived at the inn.

They parked the car, and Jack followed his father into the cluttered shop. Mismatched pieces of furniture were on display in the front window, and stacks of paintings lay against the far wall. Clocks, jewellery boxes, figurines and books filled the shelves. On the wall behind the counter hung two long menacing English broadswords.

As Jack catalogued a collection of rare books in the tiny back office, the bell above the shop’s door jangled. Jack came through to the front to see who it was. His father was talking to an eccentric-looking old man dressed in a shabby raincoat.

“A rare find, that’s certain,” proclaimed the old man, handing over a wooden box.

Jack drew closer to see what it was.

“A rare find,” the old man repeated, as Jack’s father removed an antique pistol from the box and turned it over repeatedly in his hand, feeling the weight of it.

The man was almost completely bald, but he had a thick unkempt white beard and sharp blue eyes that twinkled in his deeply lined face.

“I’ll have to take a closer look at the markings. I’ll take it into the back office,” said Jack’s father. “It’ll take a few minutes.”

The instant Jack’s father closed the door to the back office, the old man reached across the counter and grabbed Jack’s wrist with unexpected strength.

Jack was too startled to utter a word.

“The drawer of the box opened!” whispered the old man. “You found the letter, didn’t you?”

The Letterbox

II

The old man relaxed his grip, letting go of Jack’s wrist. “It was a rolled parchment, wasn’t it?”

“Yes,” said Jack, “but I couldn’t read it.”

“Never mind that. Do you have the scroll?”

“Right here,” said Jack, holding it up.

The old man snatched it from Jack, unrolled it on the counter and quickly scanned the letter.

“There isn’t much time,” he said gravely. “Here, take this.” He reached into his pocket and handed Jack a small metal wheel with a pin through the centre.

“Inside the box there is a slot where this wheel should fit perfectly,” the old man whispered urgently. “Insert it into the slot. Put the scroll back into the drawer, close it and open it again. You shouldn’t have any problem reading the text.”

“Is this some sort of joke?” Jack asked.

“Lives are at stake! Only you can reply to the letter. Speak of this to no one,” said the old man, hurrying toward the door, “not even your father.”

Before Jack could ask any more questions, the old man was gone. The sound of the front-door bell brought his father out of the back office.

“Did he leave?”

“Yeah,” said Jack, still stunned. “He said he’d come back later for the pistol.”

“Fair enough,” his father nodded.

That evening, Jack sat at his desk and flipped open the lid of the box. Sure enough, there was a slot in the centre. Jack took the small wheel out of his pocket and inserted it into the slot. It fitted perfectly.

Following the old man’s instructions, Jack put the scroll in the drawer, closed it and immediately opened it again. He took out the scroll, spread it on the desk and was astonished to see the Middle English script miraculously transform itself into modern English.

I am in desperate need. My mother told me that if I were in danger, I should write a letter asking for help and place it in this box. Whoever may find this note, I pray that you can deliver me from my prison here in the Tower.

King Edward V

June, 1483

This is way too weird, Jack thought. Could this be the same Edward that I was reading about?

He reached for his history book and opened it to the chapter on the Princes in the Tower. Once more he read about Edward and his younger brother, Richard, and how their uncle, the duke of Gloucester, had imprisoned them in the Tower of London.

I wonder if that old guy’s for real.

Jack put down the book, picked up a pen and quickly scribbled a reply.

Hi, my name is Jack.

I want to help.

Jack folded the note, tucked it into the drawer and closed it.

“Jack!” his father called. “I’m going to collect your mum from her meeting. It’s nine thirty already, so make sure you’re ready for bed when we get back.”

“Okay,” Jack called back through his open bedroom door.

He pulled open the drawer and saw another scroll. As he unrolled it, the strange writing changed before his eyes again.

My uncle, the duke of Gloucester, has placed me in the Tower where I am under constant guard. He says it is for my own safety, but I fear for my life. Do you think you can help me?

King Edward V

June, 1483

I wonder how this thing works, Jack thought, closing the bedroom door. It has to be something to do with the wheel.

He examined the wheel. He tried turning the wheel clockwise, but it wouldn’t budge. As he twisted it counter-clockwise, however, a damp shiver ran down his spine, and the lamp began to fade from view. Then he felt a lurch and was no longer sitting at his desk.

He stood in a room with stone walls and a small window overlooking a river.

On a low table in front of him, Jack saw a duplicate of the box he held in his hand. Its lid was open, but there was no wheel inside, and the artwork on the sides was shiny and new.

“Who are you?” demanded a voice behind him. “Where did you come from?”

Edward

III

Jack spun around and, hiding the box behind his back, found himself face to face with a boy who could have been his twin. The boy wore a light-blue tunic, brown leggings and black pointed slippers.

“How did you get in here? Who are you?” the boy asked, staring intently at Jack’s face. “You could be my double. Is this a plot by my uncle?”

He picked up a heavy candlestick from the table and backed away a couple of paces.

“I’m Jack.”

“The one who sent me the message? Have you come here to rescue me?”

“Are you Edward?”

“Yes. I am King Edward.”

”Then I am the one who sent you the message,” Jack replied. “But I’m not sure how I can rescue you.”

“Where have you come from? Your words are most strange. Are you not from these parts? And why are you dressed that way?”

“I’m in disguise,” Jack blurted out.

He’ll never believe the truth. I’m not sure I believe it myself.

“Why are you a prisoner?” Jack asked.

“Surely you are the only one in the kingdom who does not know,” scoffed Edward. “When my father, Edward IV, died, I became King Edward V. As I left Ludlow for my coronation, I was intercepted and sequestered here on orders from my uncle, the duke of Gloucester, who I fear seeks to take my place as king of England. The duke claims that I am being held for my own protection, but I am afraid for my life. Those who accompanied me from Ludlow Castle were arrested on my uncle’s orders. What’s worse, Gloucester has executed my father’s friend William Hastings, the Lord Chamberlain. He was beheaded right here in the Tower just days ago.”

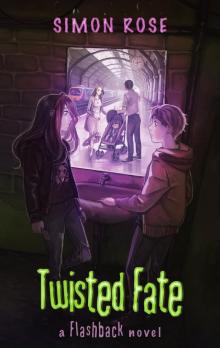

Twisted Fate

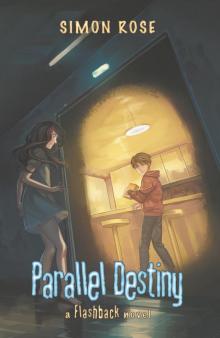

Twisted Fate Parallel Destiny

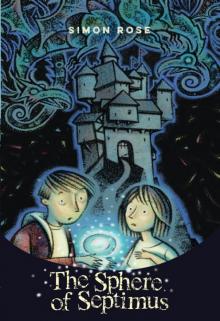

Parallel Destiny The Sphere of Septimus

The Sphere of Septimus The Sorcerer's Letterbox

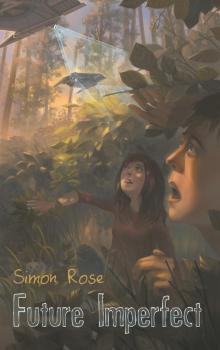

The Sorcerer's Letterbox Future Imperfect

Future Imperfect